RT25: On a scientific approach to the sustainable use of birds

Chris J Feare1 & Anne M. Haynes-Sutton2

1Wildwings Bird Management, 2 North View Cottages, Grayswood Common, Haslemere, Surrey GU27 2DN, UK, e-mail

feare_wildwings@msn.com; 2Marshall's Pen, PO Box 58, Mandeville, JamaicaFeare, C.J: & Haynes-Sutton, A.M. 1999. On a scientific approach to the sustainable use of birds. In: Adams, N.J. & Slotow, R.H. (eds) Proc. 22 Int. Ornithol. Congr., Durban: 3204-3208. Johannesburg: BirdLife South Africa.

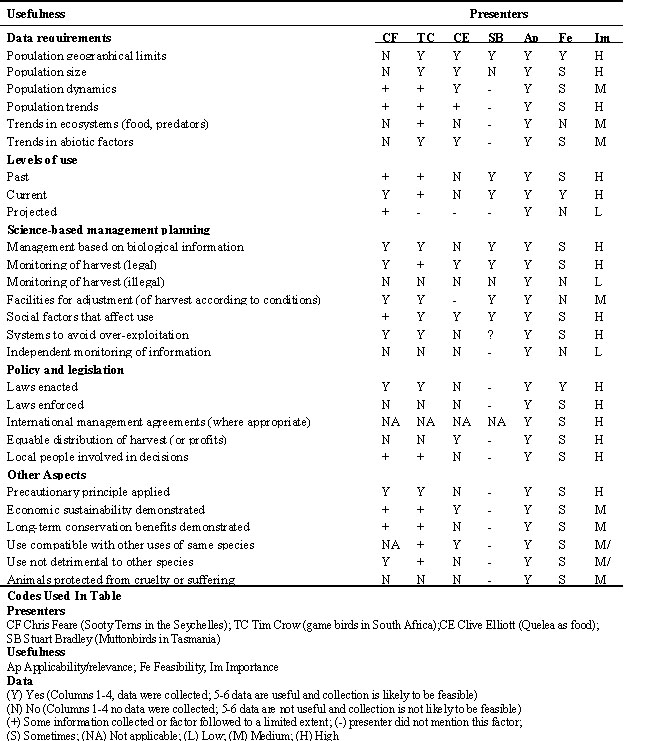

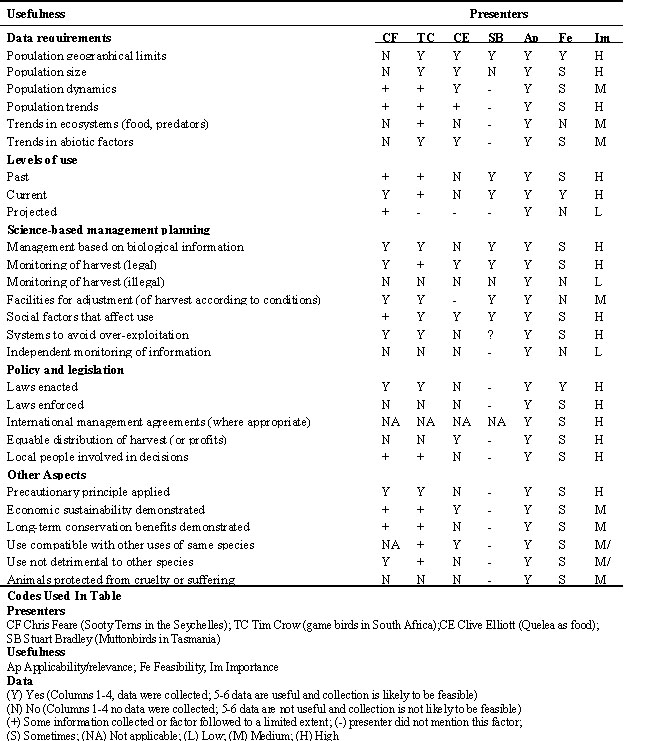

Although this round table discussion was titled as above (i.e. in the programme), factors other than science, e.g. the human social context of animal exploitation, are also important in governing whether sustainability is achievable. We therefore used as a basis for discussion, controversial criteria developed by the Species Survival Network (summarised in the table), with the aim of examining several cases of human exploitation to see how well these cases satisfied the criteria. This discussion centred on how realistic these criteria are in practice, and the extent to which shortfalls in information are likely to weaken the evidence for sustainability.

Presenters included Chris Feare, Tim Crowe, Clive Elliott, Peter Mundy, Stuart Bradley and Steve Beissinger. The level of interest in this topic, which is fundamental to many conservation and management projects, was demonstrated by the attendance of more than 30 people from at least 13 countries (including every major geo-political region except Asia).

Appropriateness of the guidelines

Several presenters found that the criteria provided a useful checklist of the types of data that they had attempted to collect and the approaches they had used to developing management strategies (Table 1). They included Chris Feare (use of Sooty Tern Sterna fuscata eggs as a resource in the Seychelles), Tim Crowe (game birds in South Africa) and Clive Elliott (use of quelea Quelea quelea as food). None of the presenters suggested that all the criteria could or should necessarily be met, but some studies had attempted to collect data on many of them with varying levels of success. Others, including Peter Mundy, dismissed the guidelines as a political ploy to discourage international trade in wildlife. He pointed out that the guidelines were promulgated by the Species Survival Network (SSN) (an organisation known to oppose international trade in wildlife) and had been rejected by several conservation organisations, including the World Conservation Union (IUCN).

It was even suggested that some notable successes (e.g. the increase in populations of elephants in Zimbabwe) have been achieved without any attempt to collect scientific data or set policies or quotas on the basis of science. A policy of using a resource until it disappears and then stopping until it recovers (e.g. hunting large horned animals until they become too scarce to hunt) may sometimes be as effective as ill-conceived attempts to manage populations on incomplete or inaccurate scientific data.

In some cases indigenous knowledge can help fill gaps in scientific knowledge and several people proposed co-operative models such as co-management and adaptive management.

Generally it was felt that scientists had an important role to play in identifying and generating the information needed for management. Some types of data are easier to collect than others. Information about geographical limits and population size in a specific area is more likely to be available than information about overall or local population dynamics and trends. Similarly data about target populations is more likely to be available than more general data about the environment. Monitoring programmes for target populations should aim to distinguish between the effects of harvest and of other pressures on the target population. Very few studies have attempted to quantify long-term changes in ecosystems and their effects on wildlife resources.

Data can be drawn from many sources. The shooting books of a club near Kimberley, South Africa have provided useful long-term data on fluctuating populations of game birds. Even where long-term data are available there are many problems with interpretation, specifically of data on population sizes, trends and dynamics. For example the population of Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris in South Africa is irruptive, showing massive fluctuations. Among Short-tailed Shearwaters Puffinus tenuirostris in New Zealand, individual birds will not necessarily breed every year if weather conditions are unsuitable or food is short. Thus there are very large fluctuations in the numbers breeding and breeding success, which do not necessarily indicate anything about annual population changes.

Incomplete information can lead to inaccurate interpretations of data. For example, an area thought to be a breeding hot spot and source for francolin populations, turned out to have very low breeding success.

The shortage of wildlife biologists and funding for studies was cited as a major obstacle to development of scientific databases on potentially exploitable species, specially in developing countries. Excessive demands for data can be used as a political tool.

Science-based management planning

Several people had experience with developing or trying to develop science-based management plans, in some cases with some success (e.g. with game birds in South Africa and Sooty Terns in the Seychelles and Jamaica). However even where data are available, there may be severe difficulties involved in translating them into management recommendations. For example the monitoring and banding programme for Short-tailed Shearwaters in Tasmania began in 1947 but so far there has been little success in developing an understanding of population dynamics.

Very little progress has been made in the development of predictive population models for sustainable harvest for wildlife in general or fisheries resources in particular. Quotas for harvest of wild birds for the pet trade in South America are often set at arbitrary levels and not based on knowledge of the biology of the species. The need to find some common ground between groups that demand excessive information and those attempting to manage wildlife resources in data-poor situations was stressed.

Importance of indigenous knowledge

The importance of indigenous knowledge about the status and trends of wildlife resources was emphasised. In Canada, the Inuit populations have demonstrated their understanding of the dynamics of whale populations and some participants urged biologists to give more credence to such sources and develop more partnerships and co-management arrangements. In contrast some traditional practices concerning harvest of tern eggs in Seychelles and Jamaica had turned out to be based on wrong assumptions when they were evaluated scientifically. For long-lived species with high juvenile survival, such as albatrosses, traditional information based on short visits to colonies is unlikely to provide the understanding of life histories necessary for management of exploitation.

Policy and legislation

Some resources are relatively well covered by local legislation (e.g. game birds in South Africa, seabirds in Jamaica and the Seychelles). Generally enforcement tends to be inadequate, for reasons ranging from economic (e.g. lack of human or financial resources), too political (e.g. lack of political will or social and political turmoil) and practical (e.g. difficulty of access to some bird habitats).

Social and cultural factors

The importance of social factors in regulating use and developing policies was stressed by all presenters. The concept of ownership of resources by stakeholders was stressed. Zimbabwe's successful CAMPFIRE programme (Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources) was cited as a case where the right policy had immediately improved attitudes to conservation programmes with no need to resort to expensive programmes of enforcement or environmental education. This was contrasted with cases in South Africa, where sport hunting had led to an improvement in attitudes of landowners to birds, but in some places local people had poisoned all game birds in protest to being deprived of their historical hunting rights. Similarly in South America local people do not have a sense of ownership of natural resources and programmes based on CAMPFIRE have not generally been successful.

While for rare, endangered and valuable species the problem is often finding a way to limit trade, for other species an increase in trade may be desirable. The possibility of encouraging consumption and export of queleas as part of a control strategy was mentioned by Clive Elliott. Huge numbers of queleas are taken and many are eaten (e.g. 75 million killed in pest control operations in South Africa 1997-8; 5 million p.a. sold for food annually in Chad and similar numbers in adjacent countries). Many of these birds are killed using the organophosphorus poison fenthion, and while tests have shown that cooking reduces residues to levels harmless to adults, people, especially children, who collect the birds from treated roosts/breeding colonies may absorb unknown quantities of the chemical through the skin. The potential for supplying the luxury food market in Japan and South Europe was mentioned. Quelea colonies also supply guano for fertiliser. Queleas appear to be able to withstand massive exploitation with very little impact. Such assumptions were once made about the Passenger Pigeon Ectopistes migratorius!

Crime and deception can also affect conservation programmes. In Venezuela a programme designed to encourage sustainable use of caimans by ranchers was creatively abused. Ranchers traded illegally harvested caimans, thereby maintaining high levels of caimans on their properties and increasing their quotas.

International political and economic factors

The highly political nature of issues surrounding use of birds was raised. Some international groups seek to prevent all trade and use of birds. This can be counter productive as some countries have found that sustainable exploitation is an important element in their conservation programmes. For some species, such as elephants in Zimbabwe, controlled use has been accompanied by a long-term increase in populations.

The effect of the global economy on trade should also be considered. The shortage of foreign exchange in Zimbabwe led to the export of ostrich breeding stock which has undermined the local trade. Production of high quality ostrich skins abroad has undercut the value of Zimbabwe's products and the ostrich industry is faltering.

Conclusions

The feasibility of sustainable use of wildlife resources is a complex issue. Economic, social and political factors and the difficulties of obtaining and interpreting relevant scientific data make this a very challenging field. Several participants agreed that a symposium on sustainable use of birds would make a significant contribution to the next IOC, and recommended that sustainable use should be added to the topic considered by the IOC's Applied Ornithology Working Group.

Stuart Bradley, Biological Sciences, Murdoch University, W. Australia bradley@possum.murdoch.edu.au

Clive Elliott, AGPP/FAO, Via delle Termedi, Caracalla, 00100, Rome, Italy. Clive.Elliott@FAO.ORG

Steve Beissinger, University of California, Berkeley,

beis@nature.berkeley.edu%Peter Mundy, Department of National Parks, Zimbabwe. mundy@telconet.co.zw

Tim Crowe, Percy Fitzpatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, S. Africa. tmcrowe@botzoo.uct.ac.za

AcknowledgementsWe thank Alcan Jamaica, the United Nations Environment Programme, Teddy and Catherine Sikakana, and the IOC for the support that made it possible for Ann Sutton to attend the meeting.

Table 1. The usefulness of various criteria of relevance to sustainable use